Tuesday, March 10, 2009

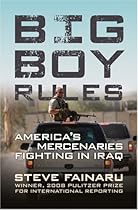

Big Boy Rules: America's Mercenaries Fighting in Iraq

Big Boy Rules: America's Mercenaries Fighting in Iraq

There are tens of thousands of them in Iraq. They work for companies with exotic and ominous-sounding names, like Crescent Security Group, Triple Canopy, and Blackwater Worldwide. They travel in convoys of multicolored pickups fortified with makeshift armor, belt-fed machine guns, frag grenades, and even shoulder-fired missiles. They protect everything from the U.S. ambassador and American generals to shipments of Frappuccino bound for Baghdad’s Green Zone. They kill Iraqis, and Iraqis kill them.

And the only law they recognize is Big Boy Rules.

From a Pulitzer Prize–winning reporter comes a harrowing journey into Iraq’s parallel war. Part MadMax, part Fight Club, it is a world filled with “private security contractors”—the U.S. government’s sanitized name for tens of thousands of modern mercenaries, or mercs, who roam Iraq with impunity, doing jobs that the overstretched and understaffed military can’t or won’t do.

They are men like Jon Coté, a sensitive former U.S. army paratrooper and University of Florida fraternity brother who realizes too late that he made a terrible mistake coming back to Iraq. And Paul Reuben, a friendly security company medic who has no formal medical training and lacks basic supplies, like tourniquets. They are part of America’s “other” army—some patriotic, some desperate, some just out for cash or adventure. And some who disappear into the void that is Iraq and are never seen again.

Washington Post reporter Steve Fainaru traveled with a group of private security contractors to find out what motivates them to put their lives in danger every day. He joined Jon Coté and the men of Crescent Security Group as they made their way through Iraq—armed to the teeth, dodging not only bombs and insurgents but also their own Iraqi colleagues. Just days after Fainaru left to go home, five men of Crescent Security Group were kidnapped in broad daylight on Iraq’s main highway. How the government and the company responded reveals the dark truths behind the largest private force in the history of American warfare. . . .

With 16 pages of photographs

Product Details

Editorial Reviews

From Publishers Weekly

For this mordant dispatch from one of the Iraq War's seamiest sides, Pulitzer Prize–winning Washington Post correspondent Fainaru embedded with some of the thousands of private security contractors who chauffeur officials, escort convoys and add their own touch of mayhem to the conflict. Exempt from Iraqi law and oversight by the U.S. government, which doesn't even record their casualties, the mercenaries, Fainaru writes, play by Big Boy Rules—which often means no rules at all as they barrel down highways in the wrong direction, firing on any vehicle in their path. (His report on the Blackwater company, infamous for killing Iraqi civilians and getting away with it, is meticulous and chilling.) Fainaru's depiction of the mercenaries' crassness and callousness is unsparing, but he sympathizes with these often inexperienced, badly equipped hired guns struggling to cope with a dirty war. Nor is he immune to the romance of the soldier of fortune, especially in his somewhat bathetic portrait of Jon Coté, Iraq War veteran and lost soul who joined the fly-by-night Crescent Security Group and was kidnapped by insurgents. Fainaru's vivid reportage makes the mercenary's dubious motives and chaotic methods a microcosm of a misbegotten war. (Nov. 17)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

From The Washington Post

From The Washington Post's Book World/washingtonpost.com Reviewed by Ralph Peters During the American struggle for independence, German mercenaries employed by the British crown terrorized rebellious soldiers and civilians with equal enthusiasm. This formative experience imprinted an abhorrence of mercenaries on our national character: We never hired our guns. Until now. As a result of its mania for outsourcing essential government functions, the administration of George W. Bush found itself embroiled in Iraq without sufficient troops on the ground and with a secretary of defense who resisted deploying additional soldiers, preferring to channel funds to private contractors. The result was the unleashing of renegades on the people of Iraq. The sadistic, too-often-murderous conduct of thousands of private security contractors -- our contemporary euphemism for mercenaries -- not only shattered critical relationships between our troops and the local population but also shamed our country. Washington Post columnist and 2008 Pulitzer Prize-winner Steve Fainaru's Big Boy Rules is the most vivid account to date of the misfits, thugs and outright psychotics who kill with impunity under corporate flags. Describing the legal vacuum that prevailed until 2007, the author writes: "They give them weapons . . . and turn them loose on an arid battlefield the size of California, without rules. . . . None of the prevailing laws -- Iraqi law, U.S. law, the [Uniform Code of Military Justice], Islamic law, the Geneva Conventions -- applied to them." Again and again, taxpayer-funded mercenaries shot down Iraqi civilians without provocation, sometimes just because "I want to kill somebody today," as one mercenary put it before going on a rampage. Much of the media and the U.S. government looked the other way -- the first because its narrative line was military failure, the latter because it was stunned when ideology collided with reality. Denied authority over the hired guns, the military seethed at the damage done to its mission. Worst of all, the State Department hired Blackwater USA (now Blackwater Worldwide), a politically well-connected firm with a reputation even among mercenaries for renegade behavior. Capping dozens of disgraceful incidents, in September 2007 Blackwater gunmen allegedly killed 17 unarmed Iraqis in a matter of minutes in downtown Baghdad, an atrocity for which five contractors were indicted this month. Afterward, the State Department still insisted its diplomats needed Blackwater for protection. The firm's contract was renewed, and "by the end of 2007," Fainaru notes, "the company had made a billion dollars off the war." Our diplomats hired gunmen to protect them, and the gunmen ravaged our diplomatic efforts. According to one Iraqi security official quoted in Big Boy Rules, "Blackwater has no respect for the Iraqi people. They consider Iraqis like animals, although actually I think they may have more respect for animals." In my own visits to Iraq, I found our troops consistently disgusted with the private security contractors, not least because our soldiers often were blamed for the mercenaries' outrages. Our troops saw outlaws, but the Iraqis just saw Americans. Not all of the contractors were Americans, of course. As Fainaru reports, the security shortfall in Iraq was so dramatic that the Bush administration blessed the hiring of dubious foreign companies with morphing names. Qualified security operatives were available only in limited numbers, so the fly-by-night firms took on virtually anyone who sought employment: military washouts, ex-cons, gunmen fired by other contractors and the utterly unqualified. Mercenaries conducted a wide range of missions, from checking identification cards at dining facilities, to guarding convoys and protecting dignitaries with pre-emptive firepower. The gunmen -- some illiterate -- came from the United States, Britain, South Africa, Australia, Peru, Uganda, Nepal and various other countries. Many of the Western hires were dysfunctional characters who could make it in neither the military, with its demands for emotional stability and discipline, nor in the civilian world. More than a few of the mercenaries were looking for trouble, and in Iraq they found it. Fainaru, who made 11 reporting trips to Iraq, deserves great credit not only for pursuing this inadequately covered, infuriating story but also for searching beyond the pseudo-professionalism of the big-name contractors to investigate the dozens of smaller outfits preying on the war. A significant portion of Big Boy Rules follows five mercenaries from the Crescent Security Group, a Kuwait-based, minimally credentialed firm that sent convoy guards into Iraq with third-rate weapons, poor communications, death-trap vehicles, no qualified medics and resentful Iraqi hires who eventually betrayed the men with whom the author traveled. The mercenaries Fainaru covered were taken captive a week after he left them. Their eventual murders were gruesome. Parts of their bodies surfaced several months later. The tale of how these men who had failed at everything else blundered into their new line of work (for up to $7,000 per month) is harrowing and well told, but it leads the author into a trap: He bonded with the "mercs" and their families to the extent that he regards their fates as tragic. Yet nothing in their public lives rose to the level of tragedy. They weren't going anyplace, so they went to Iraq. Not even Fainaru's considerable skill can make us care much about these lost souls. Nonetheless, this book is consistently engaging and powerfully instructive. As a retired soldier, I found only one (offensive) inaccuracy: Fainaru's claim that the mercenaries were "composed mostly of retired soldiers and marines." That's simply wrong. Very few of the mercenaries in Iraq had made it through full military careers (those interviewed in detail by the author either bailed out after a single hitch or never served at all). Even many of the former special-operations personnel hired by firms such as Blackwater either left the military because they ultimately didn't measure up or simply got out to grab the contractor money (a sin of the first magnitude to honorable soldiers). The gulf between those who wear our country's uniform and mercenaries is at least as wide as the gap between good cops and criminals. Attempting to excite sympathy for the mercenaries he rode with in Iraq, Fainaru reveals personal histories of feckless amorality. When these men died, their families suffered, but society did not. The Bush administration may have served as Mephistopheles, but there was no Faust among its hired guns.

Copyright 2008, The Washington Post. All Rights Reserved.

Review

"Washington Times," 2/1/09

"Compelling, brutal, disturbing."

Customer Reviews

Soldiers Good, Mercs Bad?![]()

Steve Fainaru's book on private security contractors in post-war Iraq started out as a newspaper article on the same subject for the Washington Post. I guess I should have figured that out from the way it reads. It's long on narrative but pretty short on facts.

Which isn't to say Fainaru skimps on the journalism but that so little is known about the details of Crescent Security's Iraq operations that he doesn't have much he can really report on. And as to the fate of the six security operatives kidnapped while doing convoy security? Well nothing is known at all about what happened to them after being abducted other than that they're all dead. And so with so little to go on Fainaru drags out what he does know and combines it with mawkish sympathy for this grab bag of losers and misfits who comprised the guard force of Crescent Security. At times Fainaru is condescending and at others perplexed and sometimes even angry with them and their conduct and the bad life choices that led them to their ultimate fate. But that is Fainaru's opinion and not the hard facts; the real truth isn't known and probably never will be either but at least Fainaru's speculation is informed and which should count for something.

Unfortunately I cannot recommend this book very highly as it fails (IMHO) to add to what we already know about the glaring planning and logistical failures of the Iraq war planners. But it does succeed as a cautionary tale about what fate can be in store for damn fools that put their greed and/or lust for adventure ahead of good judgment.

Shocking, Riveting, Eye-opening![]()

I am an American. I had no idea all this was going on. This is a great behind the scenes look at the lives of military contractors on the ground in Iraq. The main story is about the security contractors, but we also get a glimpse of those who hire them, the other contractors who deliver supplies and build bridges and are simply there to rebuild Iraq. Its amazing that we get anything done over there. The shocking part was how so few people will sign up for this kind of work that these companies must pay HUGE salaries and take anyone they can get, qualified or not, sane or not. The whole thing sounds like a big cluster f---. I could not put this book down. Read it in about 8 hours.

Big Boy Rules![]()

I just finished reading this book, having purchased after hearing the author interviewed on VPR. I thought the book was ok, but left me without any real feeling of conclusion. The only thing I really took away from it was if you're going to be a private contractor in Iraq/Afghanistan, you better work with a BIG company, with a LOT of fire power, good armor, and few if NO locals. Because NO ONE (including the US Govt)is coming to help you if you're in a tight situation, or God forbid captured, and the locals will sell you out for a few dollars/dinars more than you're paying them. I'm sorry for the families and their losses, but these men weren't going down South to rebuild after a hurricane, they were going into a war zone, and if they didn't go over the possible outcomes of their own choices, they were fools.

Related Links : Product by Amazon or shopping-lifestyle-20 Store

Posted by Horde at 2:00 PM

0 comments:

Post a Comment